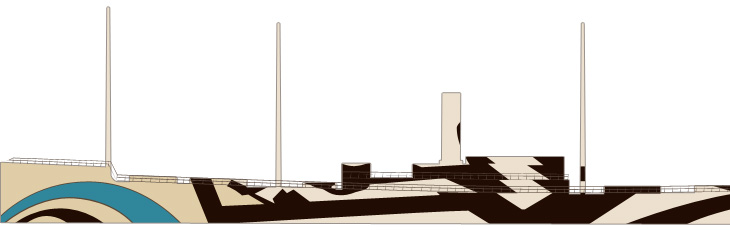

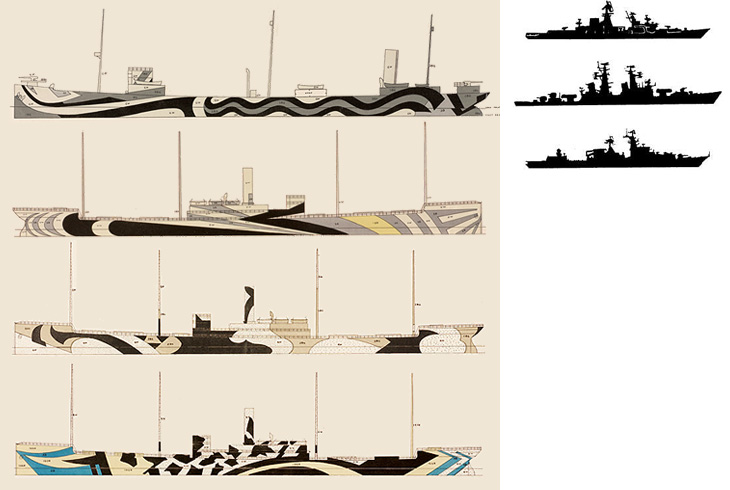

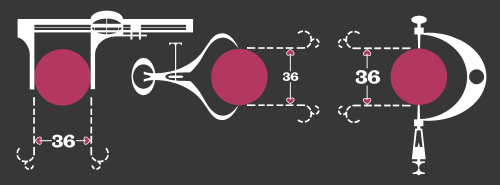

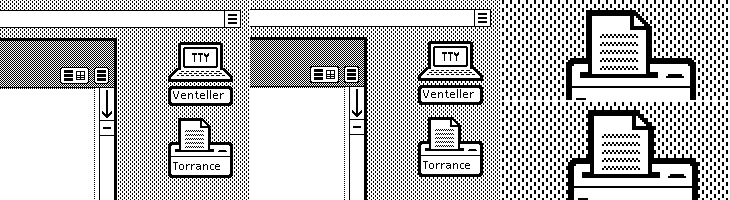

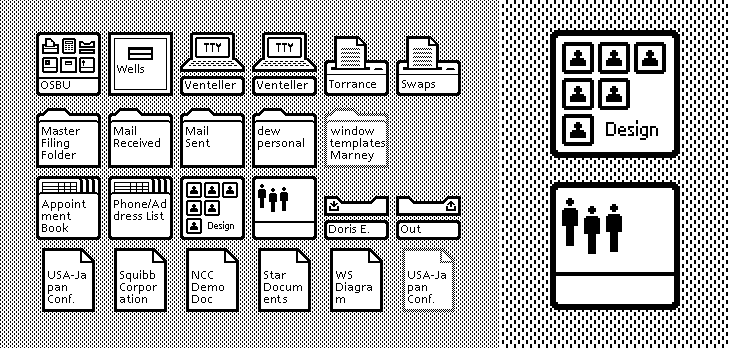

A couple of weeks ago ISO50 linked to this set of polaroids of the Xerox Star user interface on Digibarn, and I’ve been looking back at them on and off since. The UI has some interesting little details; it was designed for a two-colour display, so used a couple of dithered patterns to create the grey shading on the desktop background and window titles, which in turn created a few problems for the designers. To get a neat, crisp interface, icons and windows have to be sized and positioned on the background so that the black and white dots don’t interfere with the outlines and create a kind of blur or eye dirt effect. The polaroids show some of the design notes and instructions for doing this; it’s a lovely illustration of the attention to detail they employed to make the best of a technological limitation. Rather than recreate them directly (you can see the originals here, and here) I’ve redrawn a bit of the UI here, with ideal alignment on the left and detail top right:

If I’m to get preachy (and ranty) for a moment, I think it’s a task any designer should attempt as part of their education - what you learn from designing for such a restricted display helps with all sorts of design tasks later; you learn what causes a lot of those visual disruptions and artifacts that you catch from a quick glance or out of the corner of your eye. It may be subtle, but it’s the kind of thing that reduces the overall apparent quality of your work, the stuff that marks out your work as being standard (read: mediocre) or exceptional. If you feel you shouldn’t get precious about such things, perhaps graphic design isn’t your thing.

As others have noted, the UI at first seems remarkable for its apparent modernity, the conventions it uses are still ones we use today; with a graphical update to it you’d get a reasonable facsimile of any windowed GUI of the past few decades. The designers at Xerox clearly did a remarkable job, addressing so many design problems at once, with solutions so good that almost three decades of development haven’t significantly improved on them. We could throw up our hands as a result and say that this is clearly it, that nothing new can be done, but apart from being depressing, this would miss a couple of important (to me) points:

- The hardware configuration of a desktop computer has barely changed - we still use a mouse (or equivalent), a keyboard (however fancy and bristling with hotkeys it is) and a screen (whatever the technology, it’s still a 2D array of pixels)

- We haven’t changed - we’re still human beings.

Essentially, we are still the same configuration of limbs and sensory organs using the same configuration of display and input devices. It’s when we change either of those configurations that we see where all the real innovation has been. Adaptive and assistive technologies are developing faster and faster as component prices fall and previously isolated innovators are connected and share information online, and in tandem with this we see the spread of input technologies that enable methods such as touch, voice and gesture. We can hope that these technologies become widespread enough to change the design of the traditional desktop, or even make it obsolete, and that leads me nicely onto…

A futurist digression

Heading off into the realms of the futurist for a moment, I think a lot of attention has been given to display-related technologies such as 3D/holograms, but not even sci-fi has come up with anything really remarkable with the idea - oh sure, you can create a hologram of a keyboard, or a touch screen, but those merely address matters of convenience: you don’t have to store the thing when it’s switched off. The interfaces we see in films are mostly still all about manipulating pictograms. What I’m really interested in are the kinds of interface that use our other senses, interfaces that seem less flashy and appear almost mundane such as vibration (as in mobile phones), things like the sleep indicator on Apple computers and potentially most importantly, speech.

Forget flying cars, we’ll know it’s the future when we can talk to our computers, just like in Star Trek, but hopefully not quite like in 2001: A Space Odyssey.