TL:DR (ahem)

It’s a fantastic thing which has the potential to be very useful. You are drawing with a biro though so adjust your expectations accordingly. The software is awful, but not so bad as to make the device useless. Just make sure you export as SVG.

Far TL:DR

If you sketch a lot and need a digital copy of your sketches, get one. I’m glad I did. Actually, I’m not. See below.

Update: I discovered that Wacom believe the Sketch Manager software is so vital to your everyday computing needs that they’ve set it to launch on startup. What’s more (and I suspect this is down to the dodgy Windows to Mac port) it doesn’t do this properly, in a way you can change using the Mac OS ‘Login Items’ setting. To stop it launching at startup, have a look at this Apple Discussion entry. I found entries for Sketch Manager in both the main and user ‘Library’ folders. What’s more the user library folder is hidden, so you might want to ‘unhide’ it first. This is a terrible thing to do, requiring technical knowledge that shouldn’t be expected of any buyer of a consumer product to fix.

Update 2: I bought mine from Wacom directly. I don’t know anywhere that has them in stock. You might want to reconsider anyway, given the above.

Wacom have (finally) started sending out orders of their new product, the Inkling. I got mine the other day and I’ve been having a good play with it. It’s very good. Not perfect, but very good. The announcement video set some very high expectations, some of which are matched by reality, while some… aren’t.

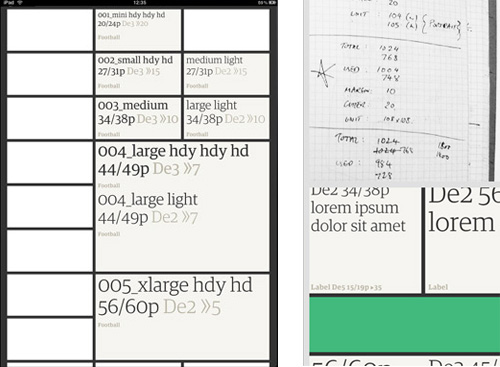

The whole idea of the device is to record what you draw so that you can import it into image editing programs later, either as a bitmap or (more excitingly) as a vector image. It keeps a track of every stroke, in the order you made them, and records how hard you were pressing on the pen, so the recorded lines vary in thickness with pressure. I think it was this that really got everyone interested.

As a gadget, it’s a lovely little thing. There’s a pen, a receiver, some spare nibs and a USB cable, all neatly packaged in a case that doubles as a charger. Closed, the case looks like a rather glam pencil case with an elaborate hinge.

Using it

Getting started with it is straightforward. You clip the receiver onto the edge of your paper (or notepad, envelope, napkin or whatever) turn it on, and draw. The pen turns on when you start drawing, though I found best to give the nib a preparatory tap on the page somewhere first, just so you know it’s ready, otherwise you’ll lose the first stroke.

The receiver has a couple of buttons, one to turn it on, and the other to create a new layer in your drawing (yes, you can create layered drawings). Turning the receiver off and on will create a new file, as will squeezing the clip – as you might do when changing the paper, which is a nice touch.

Does it actually work?

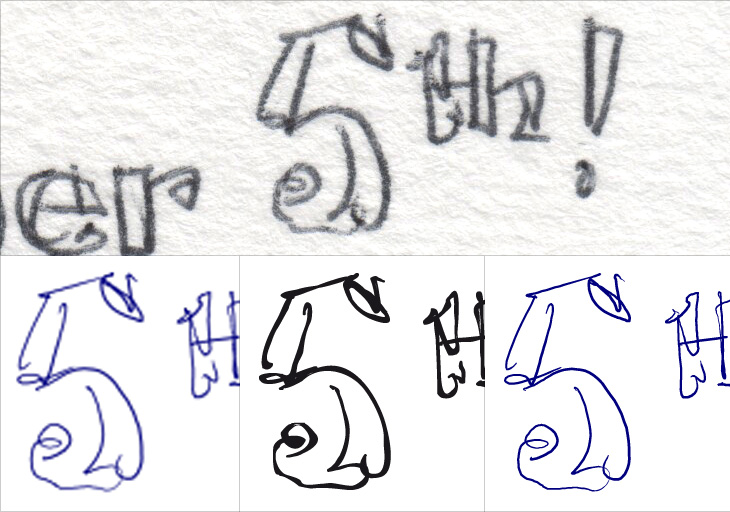

Well yes it does, rather well actually, but it does depend on your drawing style and your expectations. It does a very good job of recording your strokes, from the faintest to the heaviest of lines, and it’s as good as my tablet at recording the fairly fast and loopy lines of my handwriting. I tried a few drawing styles, from handwriting to fast and loose scribbles to a sketch of my hand, crosshatched shading and all, to see how it would record them, and for the most part it did a very good job. Looking at the vector output I can see why Wacom supplied the pen with only ballpoint tips; you can probably play with the settings to improve things but ballpoints aren’t particularly nuanced or subtle drawing devices, and the output reflects that. As I said, it records things well, but not beautifully. When exporting as SVG, the vectors are made from very short line segments (they aren’t smooth beziers) and very faint lines tend to come over a bit thick, so what you’d drawn as subtle crosshatching is recorded as a rather heavy bit of shading, while thicker lines come across as a bit thin.

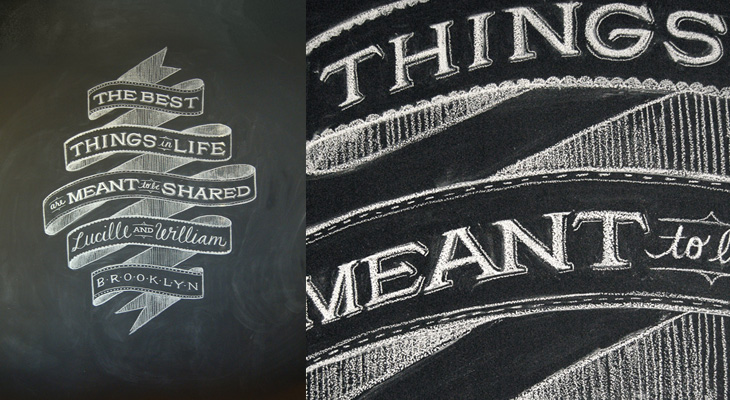

I don’t see any of this as a serious problem though. I think by making the pen a ballpoint Wacom are signalling the quality and style of drawing that the device records well. With a few tweaks to the settings, I can see myself using it to record some actual illustrations for use as final artwork, but its real strength seems to be in recording rough ideas. My sketches of lettering ideas, flow diagrams, outline illustrations, logo and site ideas all came across perfectly (though with provisos, see below) and were great to use in Illustrator as guides for finished artwork. Because the output is vector and faithfully records pen pressure it works far better than a scan might, and means I don’t feel I need to delete the guide layer to keep file sizes down (as I might with a scan).

What the device offers is convenience, and a bit of magic. It’s less hassle than scanning or photographing your notebooks, and you get scalable vectors nicely separated into whatever layers you want. You can draw an outline sketch and then feel free to scribble and annotate all over it, knowing each addition can be turned on and off and moved about at will, or even deleted entirely. That’s the real appeal of this thing.

The software

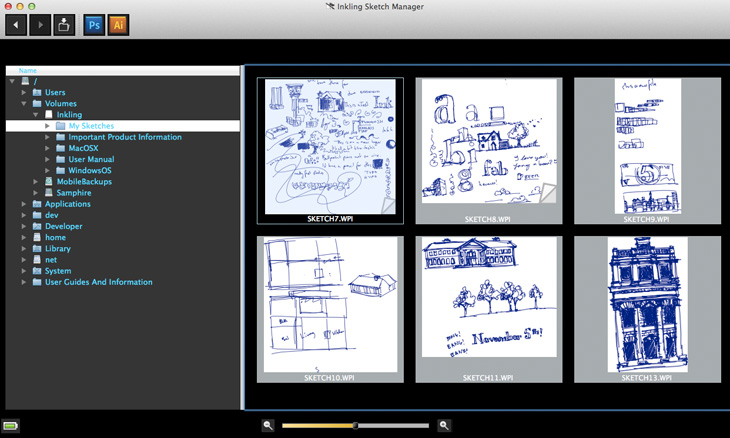

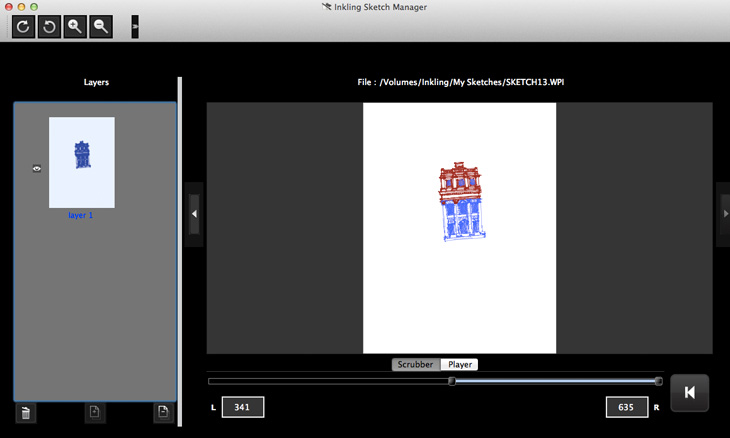

There are some extra special bits of magic the Inkling hints at, but isn’t yet backed up by the software that comes with it. When you look at a sketch using the ‘Sketch Manager’ software, you can replay the drawing process as an animation, or use a scrubber to focus on a particular sequence of strokes. There’s something quite fabulous at seeing a time lapse of something being drawn, and here it is with your very own sketches! But, and I found this a little disappointing, you can’t export the sequence as an animation. The whole purpose of the player and scrubber is to allow you to split your drawing into multiple layers, as you might want to if you’d not pressed the ‘new layer’ button at a particular point. Useful, I’ve no doubt, but a rather mundane use case compared to the “can you see what it is yet?” fun potential. It would be nice to be able to export animations, and I know it’s not the main purpose of the software, but it seemed like such a big potential win that I was surprised it wasn’t there.

The other issues with the software are less structural and more down to (it appears) a rushed job and skipped testing. The screenshots in the manual show the software running on Windows, looking fairly good, with everything looking like it’s in the right places. Seeing what it looks like on the Mac, I would hazard a guess that it was designed originally for the Windows UI, written for Windows, tested on Windows and then ported over to the Mac. Button assets look clumsy against the Mac’s grey UI, some buttons end up in the kind of drop down that you get when there’s no room to show everything and the text is jargon-filled and doesn’t feel like it was written for humans. There are some very odd labelling choices too; for example, the scrubber for the drawing timeline shows two numbers, one labelled L, the other R. Left, and right. I had no idea what these meant other than to wonder whether it was a count of left versus right handed strokes, which would be an odd thing to show since I’m fairly sure ambidextrous illustrators are quite rare. But no, as you move the scrubber bars, it shows you how many strokes are to the left of the scrubber (i.e. earlier), and how many to the right (later). I can’t imagine why this would be at once so important to show, and yet not label properly.

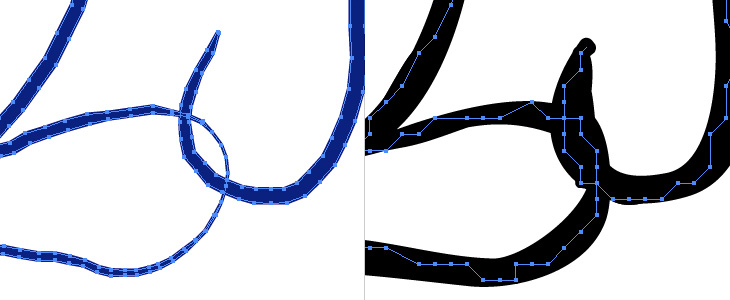

More serious problems show up when you try exporting sketches to Illustrator and Photoshop. At this point you really need to have restarted your computer after installing Sketch Manager (yes, it’s rather old school), if you don’t, Illustrator will give you a dialog asking whether you want to import the text as ANSI or not. Whatever you pick, you’ll get a large text field with the contents of an XML file in it. If you have restarted, you’ll get a series of very strange paths with stroke widths set using Illustrator’s calligraphy tool. It’s not great. Sharp corners get filled in as splodges and the whole thing looks like a vector trace of a bitmap.

Exporting to Photoshop was a bit better in that I got an actual image first time, but it created a 600dpi document with what looked like a scaled-up 300dpi image in it, which I think is exactly what it is; when you choose to export to any of the bitmap formats they create a 300dpi image. Also, when you choose to export to Photoshop, it changes your Photoshop settings so that the units of measurement are inches. I can’t even begin to comprehend the utter boorishness of this. I’ve checked, and checked again. I set my units back to pixels, export a picture from Sketch Manager, and there it is, inches again.

Not good. Really, really not good.

The only way to export vector data reliably is to use the ‘Save as different format’ option, and choose SVG. This works well, but is a faff as it defaults every single time to PNG and defaults the file location to the device itself. As I said above, the vectors are short straight-line segments rather than smooth beziers, but it does at least create a faithful replica of your drawing.

I should point out that the Sketch Manager is far better than any vendor-provided scanning software I’ve ever used. Not exactly praise, but it is something.

The upshot

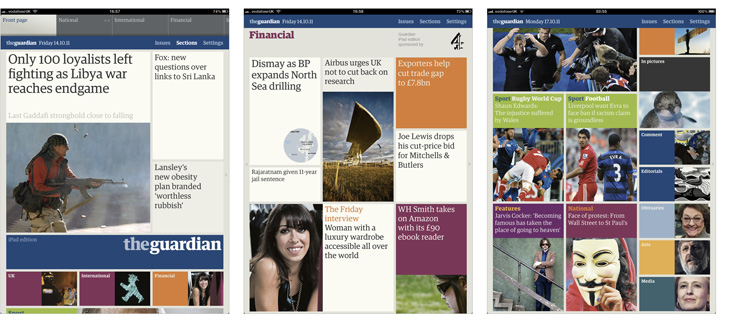

The Inkling feels very much like a tool for designers more than illustrators. If you sketch rough ideas – layouts, lettering, schematics and the like, you’ll find it very useful. If you want to record your sketchbook of illustrations, you certainly could, but it might cramp your style having to use that pen - Wacom themselves say it’s good for preparatory drawings, and I agree. I don’t use ballpoints very often for a couple of reasons – I don’t particularly like the quality of line they offer, and the ink smells bad. For the sheer convenience of this tool though, I could live with both.