What is an apostrophe? What is a quote mark? Are they curved, or can they be straight? It’s hardly a question on everyone’s lips, but it’s certainly raised the ire of people on this site, Apostrophe Atrophy (via Daring Fireball). With the link text on DF, I was fully expecting the usual suspects of grocers’ apostrophes - potato’s, orange’s, apple’s and the like - and instead finding a set of “straight” apostrophes and quotes in place of curved ones.

Call them what you will, “straight”, “dumb”, “ambidextrous” or whatever*, the apostrophes and quotes shown on the site appear (from the ones I saw) to be otherwise grammatically correct, which is reassuring. The point of the site however, is to say that it is entirely incorrect to use a straight quote or apostrophe instead of curved ones. Is it though? A comment by Michael Beiruit garnered this response:

Michael Beirut linked to us on Design Observer. He says that if people understood the difference between its and it’s he wouldn’t care what kind of quotes they use. Our opinion is that if you are setting type you should know about the correct kind of apostrophe and ALSO [sic] know about proper grammar. We have never shown html [sic]** text before, but when the site is for designers, you would think they would take the time to use the correct apostrophes and quotes…

All very true, and yet we have this, on MetaFilter. I’ve reproduced some comments here in case the page goes away:

I always turn off “smart quotes” in Word. I think it looks pretentious.I agree! Up with the “dumb quotes” backlash!I agree with the smart quotes issue. But the apostrophe thing… sometimes a dumb apostrophe looks better.Smart quotes are the fastest and easiest way to make your web page look like garbage on half the computers that visit, particularly since most designers use cute PHP tools that replace the dumb quote with the Unicode or Windows-font smart quote characters rather than with an HTML entity.

So there are people who would rather use straight quotes, for aesthetic, ease-of-use, technical and even social reasons, and their reasons do have some validity. But why do we have straight quotes at all? If they’re incorrect, where did they come from? Well, perhaps rather obviously, it’s a compromise created by the lack of space on original typewriter keyboards (more specifically, lack of space inside the typewriter for the extra workings for more keys). There wasn’t room to have an extra dedicated key for left or right quote/apostrophe marks, so a single key was used for a new “ambidextrous” set of quotes and apostrophes. As typewriters were a way of getting words hammered onto a page; faster than a scribe, easier to read than most people’s handwriting and always consistent, no matter who was doing the typing, this compromise was acceptable. If you wanted to publish your words, you would send it to a printer where typesetters would take your words and use their typographic skills to make them readable and (hopefully) beautiful.

With the advent of word processors that do everything except what you wanted to do, people are used to picking a font, typing their stuff and printing it out. The operative word here is typing. The keyboard still only devotes one key to the two symbols, and they are used for mathematical primes, feet, inches, minutes, seconds and arc as well as quotes and apostrophes. It’s up to the program you use to work out the context and hopefully replace it with the correct typographic entity. Of course, not everyone agrees that this is desirable:

For the better part of the twentieth century, the distinctive forms of typewriter type (notably its single-character width and unstressed stroke) characterized the immediacy of thought: getting the idea down without dressing it up. Now that computers have replaced typewriters, most word processing programs default to Helvetica or Times Roman (or their derivatives) as the typographic expression of simple typing. [...] As a typographer, you should recognise the difference between typing and typesetting. Time and usage may ultimately make Inkjet Sans the expected typeface for letters. For now, however, on paper, typewriter type is still the best expression of the intimate, informal voice - direct address. Imitating the formalities of typesetting in a letter is always inappropriate because it suggests an undeserved permanence - the end of a discussion, not its continuation. John Kane, “A Type Primer”, p85

So why the problem? Why do some people prefer straight quotes? Perhaps it has something to do with how the symbols are perceived. If you type something and the program you’re using changes it, then your first reaction may well be one of resentment, “How dare this program claim to know better than me!?” If what it changed it to is better, for example, a spelling correction, then you will accept it and move on. However, if it made what appears to be a superficial change, a stylistic correction, then it is more likely your resentment will remain, and you’ll go looking for that know-it-all option in the program preferences and self-righteously turn it off. I’ve done stuff like that before, and I doubt I’m unique with it! Curved quotes are perceived as ‘proper’, the kind of thing that people who publish things for money would do, people who care about such details. To use them in your work might make people think that you are one of these people, and we end up with the first quote above: curved quotes are pretentious. Think how this consideration would influence companies when they create their advertising, their billboards, their brochures and leaflets.

There are also a few technical reasons for preferring straight quotes - the main one being that they exist in “low ASCII” and no special codes or character encodings need to be used to show them. This is important consideration when programming, but is just a convenience for the lazy when creating (say) web pages. I keep my browser encoding in UTF-8, and frequently come across pages where the encoding is different from mine and the page hasn’t been put together properly with this possibility in mind. I’m left looking at a page with loads of question marks and “unrecognised character” marks everywhere. There’s no excuse for getting it wrong accidentally. Most word processors will automatically replace the straight quotes with curved ones, and for online editing, most CMS tools will automatically insert the correct HTML entities so that the symbols appear consistently on all browsers, and will usually handle (say) Word’s smart* quotes perfectly well too.

In the end, I would say that of course it is always preferable to use type correctly, but typography is the servant of meaning, not the master. If straight quotes, however much of a modern bastardisation of type they may seem, enhance the meaning of a piece (or if curved quotes would distract the reader), then you must use them. Otherwise, don’t.

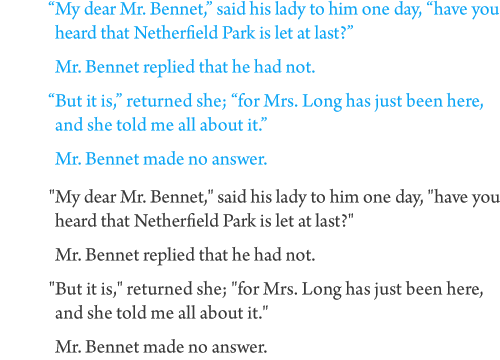

From Pride and Prejudice, on the low-ASCII and straight-quoted Gutenberg Project.

* I absolutely refuse to use the terms “smart quotes” or “dumb quotes”.

** Capitalising ‘also’ but not ‘HTML’ is unfortunate, for a site so apparently devoted to correct typographic usage.